When I was growing up, soccer wasn’t very big in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

"We had no idea."

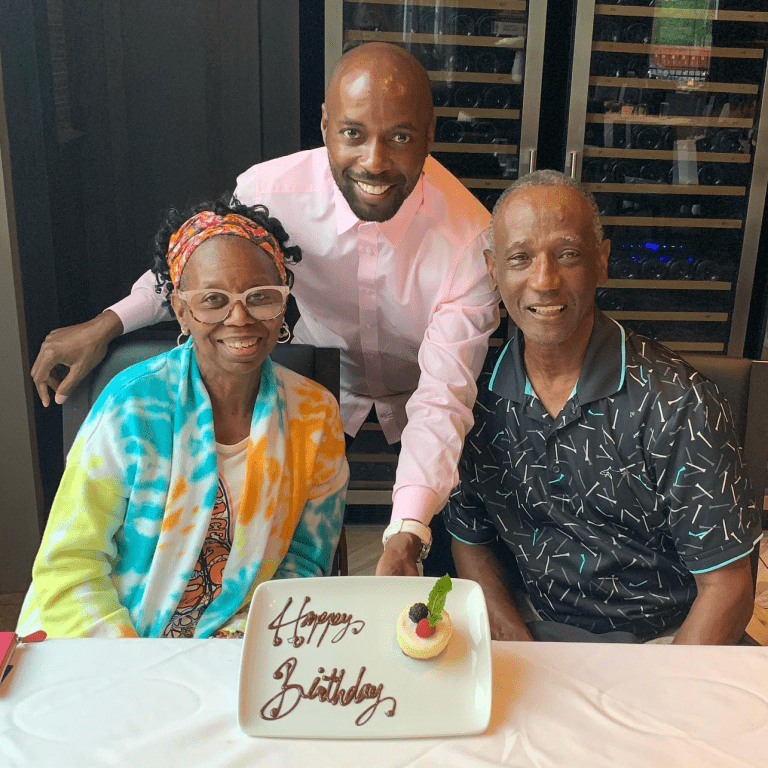

My dad was my coach in the beginning, until we learned that there was actually soccer being played outside of my backyard, with me and my brother Jamar. We had no idea. My dad just kind of brought home a ball, we started kicking around the backyard, and that’s how we got into it.

When you're young, you never look at it as you're the only Black person playing soccer. I just wanted to play and have fun with my friends. When we started traveling around Indiana, Michigan and Ohio to play different teams, WE were the diversity! You would rarely see other Black players in the Midwest, and you could count on one hand the number of Black kids on my high-school team. But it just never really hit me at that time.

There wasn't social media and there wasn't a lot of coverage around the game. There wasn’t even a fully professional league until MLS launched in 1996. But with the ‘94 and ‘98 World Cups, you saw what soccer could be in the United States. And for me, seeing Cobi Jones and Eddie Pope on a national stage made me feel that I could do that as well. Seeing Black players at a level where I was trying to get to? That inspired me to keep going, to keep playing.

Obviously, my brother was a big part of that as well. I don't think many people know this, but Jamar was the first-ever player to sign with MLS straight out of high school, in ‘98. So just having that connection and having that closeness with my brother and seeing him go through being a professional athlete, starting with the New England Revolution, what he endured, good and bad, it was an eye-opening experience for me.

Encountering real racism

When I was 15, 16, thinking about my next move in my career, deciding whether I was going to go to college or turn pro, seeing that professional level up close, going to games and training sessions, seeing how the professionals acted – I think that was a big part of why I wanted to play the sport. And everything hit another level after I moved to Bradenton, Florida to become part of U.S. Soccer’s new Under-17 residency program alongside guys like Landon Donovan, Oguchi Onyewu and Kyle Beckerman.

The experience that we had down there was amazing. It didn't always go smoothly. We missed our families. There were fights and bickering now and then. But at the end of the day it was always love because we all shared the same goals: first, to win a U-17 world championship, second was to play professionally. We always knew where we wanted to go. We were only 16 years old, but we had so much responsibility for ourselves. Getting up on time, doing your homework, chores – there was no mom and dad telling you to do this, to do that. We had to grow up from boys to men pretty quickly.

Bradenton was also where I first encountered real racism. And I remember the exact words. I was having a discussion with two other students, one a young lady and the other a young man. And the woman, she said, ‘You know, you're Black. Your skin color is the color of mud.’ I was like, oh, OK, all right. And that was probably the first time that I experienced racism as right in my face. You see it on TV, your parents tell you the dos and don'ts of what you can and can't do, they try to protect their children. But to have that thrown in my face right there at a young age? That was eye-opening.

First black coach

I signed a “Project-40” (today it’s called Generation adidas) contract in 1999 – I was still finishing up my high school courses – and got allocated to the LA Galaxy. But before I’d even played a game for them, I got a call from their coach, Sigi Schmid, God rest his soul. And he tells me that he’s going to trade me. I was like, ‘Oh, really?’ And in my head I'm thinking, 'Man, what did I do wrong?'

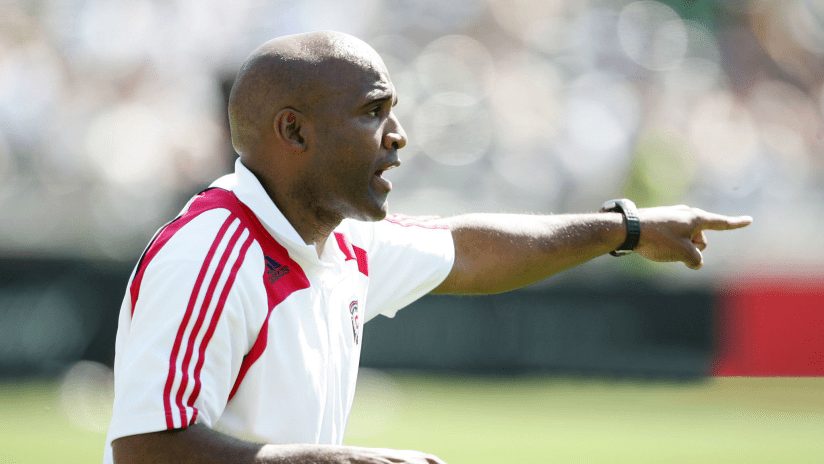

Looking back on it now, though, it’s wild that I didn’t have a Black coach until I joined the Chicago Fire.

That was Denis Hamlett, our assistant coach under Bob Bradley. I remember Denis coming to talk to me and saying, ‘Hey, if you really want to be better than you are now, you have to work on your game.’ He went above and beyond. I would come to training early to work on different movements, different shooting and finishing exercises, my right foot, other things I needed to improve. I would do it all before anyone came to training, and this is when I was 17, 18 years old. Denis saw potential in me, and took it upon himself to say, ‘You need to work on these things if you really want to play on this team and be consistent and go play at a higher level.’

In Chicago, I never felt out of place because I was Black – and I think it was because I was surrounded by Zack Thornton, CJ Brown, Evan Whitfield, Damani Ralph, Dipsy Selolwane and guys like that early in my career. I consider myself lucky to have gone into a positive, success-oriented environment like that Fire group. And it was from top to bottom, not just the players but the front office, the ownership; Peter Wilt, he was the president at the time, the coaching staff, the mentality that we had was special. That prepared me for my next step, moving to Europe and playing for PSV Eindhoven, Manchester City and Rangers.

Much later, towards the end of my career, I had younger guys like Maurice Edu, Jozy Altidore, Fafa Picault, many of whom are also my dear friends, tell me, “Man, I played this game because of you,” or “You were the first Black guy I really related to and showed me I can make something of myself in this sport.” Really, I never looked at myself in that way, that I was a so-called trailblazer or someone that's moving the needle in the Black community. I never thought of myself as a role model. I always just tried to play the game in the right way, to give back when I could, give back to my hometown with my camps and different things like that. It gave me goosebumps to hear that I had inspired others to go even further.

In retrospect, my generation did our thing more so on the field. We were trying to create opportunities from a playing standpoint, give other Black players the opportunity to play in Europe or MLS or the inspiration to play on the national team, and we were following in the footsteps of Cobi and Eddie, and Desmond Armstrong even before them. We were trying to take another step forward, to bridge that gap, change that narrative that soccer was just a white suburban sport, and get more African-Americans to play the game and to fall in love with it.

Today's players

But today’s MLS players, what these brothers are doing is going above and beyond that, and that's what I love about their initiatives like Black Players For Change and what they stand for. I tell them all the time, what they're doing is really remarkable, and it’s inspiring me as an elder statesman.

We’ve seen all too often over the years how a tragedy like George Floyd’s killing can happen and then after two or three months, it's kind of brushed under the rug. No – Black Players for Change is different. They mean business. They're really trying to leave their legacy, on and off the field. And these are young brothers. These are not 40-, 50-, 60-year-old men, these are young African-American players and ex-players that are leading this charge. That’s what I love about their organization. They’re young, energetic, intelligent, they know what they want, they're organized, they're really trying to effect change in the right way, in a positive way, to move that needle.

I’m optimistic about what MLS is doing now, and the people that they’ve put in place to help the BPC and better connect with the Black community, and that's on the field, off the field, the C-suites, different initiatives that they've partnered with. There wasn't much of that back when I started playing. I don't think they were positioned to do what they're doing now 15, 20 years ago.

But today I see a commitment to grow and evolve, to stand up for justice and build more representation at all levels of the game. It would have been a mistake if MLS had responded to the tragedy of George Floyd with just a few social media posts and t-shirts and captain’s armbands and little things like that. But they're putting the money where their mouth is.

For me, it's always about action more than words. We've all seen how different organizations and clubs can put out a tweet against racism and discrimination. But when this thing has really hit him right in their face, how do you respond to that? How do you respond to those things happening to your club? Are you being active and proactive in trying to prevent things like that? Do you have people of color in positions of authority like you do in key positions on the field?

It’s not an easy road, and there’s so much work to do. But when I look at our soccer culture today, I see the huge steps forward we’ve taken and I feel hopeful about the future.