While they’re hardly the only MLS academy that fits the description, it’s probably fair to call Orlando City a sleeping giant when it comes to youth development and homegrown cultivation.

It’s not that the Lions haven’t prioritized this area. They’ve invested substantially in infrastructure, including top training facilities and their second team, Orlando City B, and have tried out different approaches like a partnership with the Soccer Institute at Montverde Academy, a residential academy linked to a nearby private school. Orlando even signed their first HGP, Tommy Redding, a year before they played their first MLS match, and have five homegrowns on their current roster – one of whom, Benji Michel, took part in the US men’s national team’s just-concluded January camp.

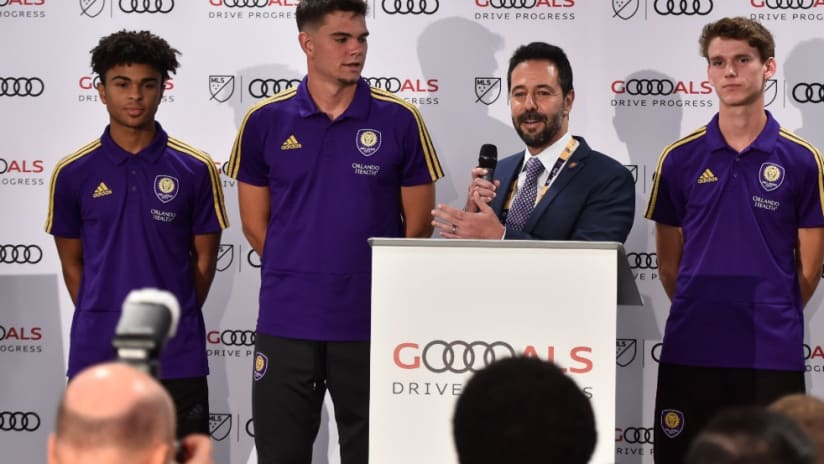

But considering their diverse, talent-rich Florida surroundings and year-round training climate, there’s a distinct sense of unrealized potential left on the table. A glance at the track record of Oscar Pareja and his coaching staff as well as EVP of soccer operations Luiz Muzzi (pictured above, middle), now entering their second year in charge at Exploria Stadium, only reinforces that. That duo were instrumental in goosing FC Dallas’ academy structure into overdrive during their five years at the helm in Frisco, an effort that continues to bear enormous rewards for the North Texans.

Which is why OCSC’s recent announcement of a new initiative, dubbed the “Orlando City Youth Soccer Network,” to better connect with their region’s youth soccer communities, bears watching.

“This work was already being done here before I got here, before Oscar got here,” Muzzi explained in a recent conversation with MLSsoccer.com. “We just brought something that we really believe in. We are strong believers in that model.

“This is a good place for kids to play. And we just want to make sure that everybody has a methodology, has a plan, has a curriculum, has access to our coaches, to our players – and we have access to their players. All in all, it is just something that makes sense.”

The OCYSN recognizes a hard reality of American youth soccer: That it is simultaneously a developmental environment for aspiring prospects and a multi-billion-dollar recreational industry, with myriad levels of competitiveness and commitment from toddlers to college kids. The Lions want to build more meaningful relationships on both fronts, in order to cultivate future professionals and future fans alike.

“Everybody wants to make this a stronger club in every possible sense of the word,” said Muzzi, “not only all the benefits that we get on the field, for being able to develop kids and get those kids to be better players and eventually play for our academy, eventually play for our first team. But the ones that are not going to be players, they're going to be fans for life, they are going to be people following the club, no matter where they are.”

Youth soccer can be intensely political, with keen competition between clubs not only on the field of play but in recruiting, retention and economic terms. OCSC hope to transcend that by opening up opportunities for the most promising kids to enter the pro pathway regardless of their affiliations and share their resources with others further down the pyramid.

“There's always a challenge of developing talent vs. the business that some of these youth programs are just worried about the money, and that's where you start creating friction. But I think this is actually getting a lot better,” said Muzzi.

“Anywhere in the world, you want your kids to play for the top teams. You're in, I don’t know, Italy, and Juventus comes by and says, ‘hey, I'd love for your 12-year-old kid to play for my team.’ That would be an honor. So I think that the youth system here is kind of slowly realizing that both can work together, both like the top teams getting talent development and the business of, there's some kids are not going to be professional players, but they enjoy playing the game and they can benefit from after-school programs and they can play in that neighborhood soccer club and make friends and get a college scholarship. I think there's space for everybody. We just need to work together.”

Orlando City SC youth academy players huddle up prior to a match. | Courtesy of Orlando City SC

Much like the Dallas/Fort Worth MetroPlex scene that Muzzi and Pareja utilized at FCD, Florida is one of the United States’ true soccer hotbeds. Even though the arrival of Inter Miami has cut off Orlando’s access to South Florida talent, they see tantalizing possibilities in their catchment area across the central and northern parts of the state, starting with their own backyard and working out from there.

“There's so much talent,” noted Muzzi, in terms of both natives and transplants. “There's people coming from different parts of the world to live here. So we get some of that talent as well, and a lot of those kids, they move here because their families move here, and they come in when they are really, really young and yeah, they were not born in this country, but they grow up here. There's lots of families like that here: You look at a 12-, 13-year-old kid and the kid has been here since he was like 3 or 4. There's a lot of players that come here and they stay here when they retire.

“We need to know what we have around us, right? It's a little bit of the concentric circles theory. And you start going out, expanding out, but you can’t get to that final circle, which is really really far away, if you don't control the immediate, close-in circle, if that makes sense. That's what we're trying to do.”

At first-team level, Pareja engineered a dramatic turnaround in his first year in charge, steering the Lions to the final of the MLS is Back Tournament and their first-ever Audi MLS Cup Playoffs qualification. Factor those results in with his and Muzzi’s priors at the cutting edge of the wider renaissance of North American talent prospering on the world’s biggest stages, and Orlando may have the makings of another “Play Your Kids” success story at hand.

“I think people just realize that there's a lot of talent in the American player,” said Muzzi. “Today people are realizing that, hey, there's a lot of good players and good kids here. And those guys can be world-class players. So the investment makes sense, it just makes sense. To me, it took too long. It's getting better. But it can get much, much better.”