The Dutch did not play anywhere near as well in the group stage of this tournament as their talent suggested they should’ve. They were always outshot, frequently outworked, and almost always looked like they were on the verge of collapsing against both Senegal and Ecuador.

That was not by design. They genuinely struggled, and those struggles laid bare the fact this Dutch generation is nothing like the heavy possession, free-flowing Dutch of 2010 or 2014, let alone the great, Total Football sides of Johan Cruyff from 50 years ago. They just can not play like that.

What they can do, however, is plan like hell, absorb a bunch of pressure because of their world-class defense, and then take advantage of any/every gap that opens up (or that their game plan opens up for them) on the field.

And, well, that was the story in the US men’s national team's 3-1 loss on Saturday in the Round of 16 to an Oranje side that bent when it had to, but never broke and, throughout, dispensed a painful lesson to a young, proud but ultimately overmatched US side.

Their 2022 FIFA World Cup run is over.

Gregg Berhalter is a very good coach who’s had a very good tournament, and will go on to do very good things somewhere (I’m one of the many who think he will leave the US program for a club side in Europe in the coming weeks). Louis van Gaal, however, is an all-time great, world-class manager who is one of the authors of the modern book of soccer tactics.

Van Gaal’s chapter would likely be “how to play a possession-heavy 4-3-3,” though today’s lesson was “how to play against a possession-heavy 4-3-3.”

There were two basic principles we saw in the structure of the Dutch shape and system on the day:

- Man-mark the midfield. This took away the kinds of tick-tock, metronome-style passing sequences the US had used to such good effect in the first hour of all three group-stage games, and forced the US backline into either dangerous cross-field passes (mostly Tim Ream to Sergiño Dest), or long balls toward the front line the US were never going to win.

- When they got on the ball – in the first half, anyway – they had an unusual amount of possession deep in their own half, with the goal of creating “pressure traps.” In other words, they wanted the US to come press the ball in order to drag them upfield and create space to attack in behind.

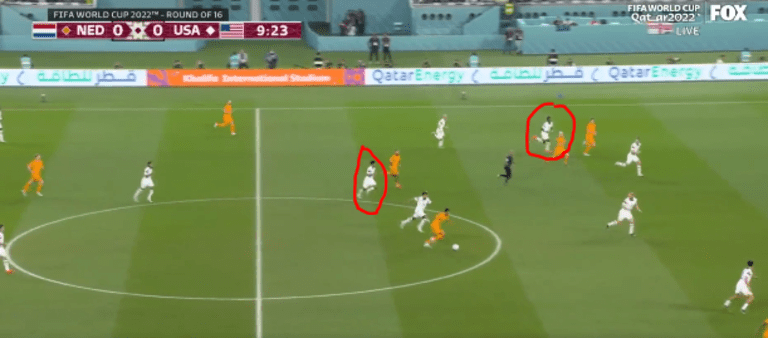

And, well, here’s what that looks like:

This didn’t lead to outright domination despite the disappointing scoreline. But it did lead to the game’s opening goal (that’s the graphic above), and that’s the point of tactics, right? To put your team into a better position to put the ball into the back of the net.

The flip side is that even with all of the above, the US players absolutely had their chances, including and especially Christian Pulisic's early look on goal that was well saved. Every tactical set-up concedes something; in Berhalter's case, he sacrificed the wings in order to try to control possession, tempo and where on the pitch the game was played.

By setting up as he did, van Gaal conceded individual moments. His gamble, in man-marking everywhere (but especially through central midfield), is that his guys would execute individual moments at a higher level than the US kids could.

And they did.

You’ve seen the passing map on that masterpiece of a goal. Here’s the clip:

Van Gaal’s tactical approach created the conditions in which the Dutch could push forward like that, but the players in Oranje have to make it work, and the players in Red, White & Blue have to make it as hard as possible to put a move like that together.

The US didn’t, and the two guys most culpable were Tyler Adams and Yunus Musah. Adams gets beat by Memphis at midfield, turns his head to lose track of him, and never gets out of a jog getting back:

Musah, who you can see circled at the top of the above frame, is supposed to rotate over and cover the central channel when Adams is pulled upfield. He recognizes it way too late:

You can’t give a striker like Memphis that kind of space in the box. You can’t give any decent striker that kind of space in the box.

Can’t say we haven’t seen this before, though:

Adams is 23, and Musah just turned 20 this week (he’s in his first year as a full-time central midfielder at the professional level). Both guys will improve over the next few years.

As for the second Dutch goal, this one was more predictable. Dest is a wonderful player whose defensive awareness has improved significantly. But he still has awful moments, particularly with his propensity to fall asleep at the back post and let wingers (or wingbacks) get across him to earn a chance.

We saw it twice in the second half against Iran, which is what led Berhalter to (correctly) switch to a 5-4-1 in that game. But those chances were on the film, and Daley Blind’s clever as hell, and…

That, just before the half, is a catastrophe. And while it didn’t make the second half academic – the US fought like hell, and I think everyone should be proud of this group – it really did seal the deal.

Dest, of course, is also a young player, and as I said, he’s already improved a bunch over the past few years. I have no reason to think he won’t continue to do so.

Depth! If there was one thing that was made clear throughout this tournament, it’s that the drop-off from the central midfield trio of Weston McKennie, Musah and Adams to their back-ups – at least the back-ups Berhalter brought – was precipitous. This is not a dig against Kellyn Acosta, who I think has proved to be the right guy to back Adams up as a No. 6, but he doesn’t bring much to the table as a No. 8.

Cristian Roldan and Brenden Aaronson, meanwhile, are wingers at the international level, as is Gio Reyna. Luca de la Torre was probably the only like-for-like among the No. 8s, but he picked up a knock in the weeks before the tournament, and it seems like that was that, doesn’t it?

Any of Eryk Williamson, Paxton Pomykal or Keaton Parks, all three of whom 1) cover a ton of ground, 2) win the ball and 3) progress the ball, would’ve helped so much. My biggest frustration with Berhalter doesn’t have anything to do with this game or this tournament; it has to do with what I would consider being questionable talent ID and integration among his central midfielders.

And those guys needed to be there, because McKennie (injured) and Musah (just clearly not the fittest kid at this point in his career) were gassed by the hour mark of the first three games, and they were leggy (sloppy touches and second to basically everything) from the jump in this one.

I get why Berhalter ran them into the ground in the group stage. But if he’d been more realistic in his assessments of the squad depth, I think he could’ve brought a stronger group that would’ve kept the starters fresher for this game.

The same applies at left back (poor Antonee Robinson, who basically had to sprint an entire marathon every game) and center forward, where both Jesús Ferreira and Haji Wright – despite his utterly hilarious goal – struggled to make a positive impact.

The story of the next four years will be how much the likes of MMA, Dest, Reyna, Josh Sargent, Tim Weah and the rest of the starters can improve. But the player pool needs to keep growing, and whoever the coach is has to be able to integrate new faces, be they young or old, in a way that can make the US the fresher team come the 2026 knockout rounds (on home soil).

And in the end, that’s the bare minimum four years from now. Berhalter wanted to change the way US soccer is perceived around the world in this cycle, and I think he did. But part of that changing perception means a change of expectations.

That’s the most important lesson of this painful, but not entirely unexpected loss. It’s a good and necessary one, and it should serve both the coach and the team well in the cycle to come.